A.A. Collins:

Eric Roling

Amateur Radio:

- Article

- Receiver Article

- Transmitter Article

- Article

|

Early amateur radio operators were mainly hobbyists, but there was a sense of discovery during the infancy of radio that provided something more. Radio was the new thing, comparable to what computers mean to technological whizzes in the 1980s. And like the computer hobbyists of today who are writing their own programs and building their own equipment, amateur radio operators in the 1920s were contributing to the knowledge of practical aspects of radio art. One person caught up in the excitement of radio was Arthur Andrew Collins. Born in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, on September 9, 1909, Collins moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, at an early age when his father, Merle (or M.H. as he preferred to see it written), established The Collins Farms Company there. With the Collins Farms Company, M.H. Collins brought new ideas to the stoic profession of farming. The elder Collins reasoned that the efforts of scientists and engineers could do for farming what they did for nearly every other industry in America. “Why not manufacture food for the American consumer as cheaply as motor cars and radios are manufactured?” M.H. asked in a publication which explained his new ideas. “Why not produce food on a large scale by intensive farming methods in Iowa, where high yields could be obtained and at a low cost?” The primary object of the farm company was to produce grain at low cost. M.H. Collins felt that too many farmers mixed grain production with livestock raising, and as a result, both were unprofitable. |

|

|

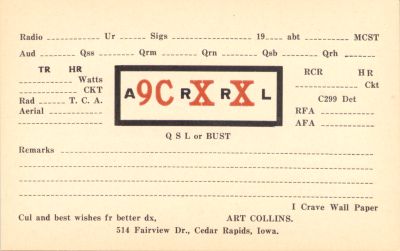

He implemented his plans by convincing landowners he could improve the profitability of their tenant farms. Farms of 160 to 320 acres were planted to a single crop and were rotated as a single tract in a unit group of farms, each embracing 1,500 to 2,000 acres. Each unit of contiguous farms was put under the supervision of a salaried foreman who directed the tractor operators. The most modern machinery was employed for every operation - four-row cultivators rotary hoes, deep disc plows, two-row corn pickers, fast trucks for marketing crops, and semi-trailers for moving machinery. For maximum use of all this new machinery, electric lights were placed on the tractors, allowing round-the-clock operation. Other practices initiated by The Collins Farms Company included installing drainage tile, erecting fire-proof ventilated grain storage bins, and using legumes to replace nitrogen in the soil. At its peak the company operated 60,000 acres of farmland in 31 Iowa counties, with wealthy businessman M.H. Collins at the helm of the corporation. At about the age of nine, Arthur Collins became deeply interested in the new marvel of radio, although at first M.H. apparently did not think highly of his son’s tinkerings with radio. Arthur and another early boyhood radio devotee, Merrill Lund, made their first crystal receivers at the Lund home at 1644 D Avenue in Cedar Rapids. The sets used variable condensers inside a tube. Merrill’s father worked in the tube department at Quaker Oats Co. and made tubes of the size the boys needed. Using thumb tacks for contact points, they wrapped wire around the tubes. From iron plates they fashioned their own transformers, and rigged a 60-foot spark antenna with a lead-in through a basement window of the Lund home. Merrill’s father asked them to find another location for their equipment after lightning struck the radio set and blew it up. Arthur brought over two coaster wagons and the two boys transported the damaged equipment to the Collins home at 1725 Grande Avenue. Although M.H. did not approve of the mess it was going to cause, Arthur hauled the equipment to his room once his father was out of sight. “I used a Quaker Oats box to wind the tuning coil and used a Model T spark coil,” he told a New York Times reporter in 1962. “The main piece of the station’s machinery was the transmitter. Other parts of the station were recruited from a rural telephone service. The way we calibrated was to pick up signals from WWV (the Navy’s station in Arlington, Virginia).” Arthur also used pieces of coal or coke for a rectifier, glass towel racks for insulators and a toy motor. Those early efforts reflected a lot of experimenting that led to successively more reliable, higher-performance radios. Another boyhood friend in Cedar Rapids who also had an interest in radio was Clair Miller. The article quoted another neighbor’s recollection of early days in the Collins family neighborhood: “We sensed that Arthur was different, but we did not know that he was a genius. When the rest of us were out playing cowboy and Indian, Arthur was in the house working on his radios.” One day Arthur’s mother invited the neighborhood boys into the Collins home. “I think she did so because she wanted us to realize that Arthur was different from the rest of us. We went upstairs to see what he was doing. He had a room that overlooked the yard. It was loaded with radio stuff. We knew a little about radio. We had been playing around with crystal sets ourselves. But Arthur had one wall covered with dials and switches, everything under the sun.“ The Federal Radio Commission, the predecessor to the Federal Communications Commission, passed a radio act whereby amateurs could get licenses. Arthur took the test and got his license in 1923 at the age of 14. As M.H. Collins recognized his son’s talent and ambition toward radio, he looked for ways to help with Arthur’s hobby. In about 1924, Arthur’s father purchased a new tube costing $135 and other high voltage equipment. “When I was a youngster there were two real active amateurs (in Cedar Rapids),” Arthur recalled. “One was Henry Nemec and the other was Clark Chandler.” Collins and Leo Hruska, another friend who had constructed a crystal receiver, used to receive the stations of Nemec and Chandler, and considered their talks with the more experienced radio operators quite an achievement. Nemec recalled how he first met the young boy with the extensive radio knowledge. M.H. Collins had asked Nemec to meet with his son so Nemec could teach Arthur some of what he knew about amateur radio, “But there wasn’t much that he didn’t already know,” Nemec said. In a 1978 interview for an article about Henry Nemec in the Cedar Rapids Gazette, Arthur Collins recalled the early days when he purchased a vacuum tube from Nemec, and several years later when Nemec, who worked for the police department, and another patrolman, Frank Bukacek, parked their squad car in front of Collins’ house while the three were inside talking radio. Collins said he, Nemec and Bukacek got together so frequently, and the squad car was parked in front of the house so often, that neighbors began to wonder whether Collins was in some kind of trouble with the police. At the time there was little formal instruction in the science of radio. Several two-day short courses were given at Iowa State College at Ames, and Arthur is said to have attended the first of these while still wearing knickers. Carl Mentzer later sponsored a course in radio at the University of Iowa. These courses, along with several periodicals, including Wireless Age and QST, comprised most of the current radio knowledge of the time, other than word-of-mouth information. By the time he was a teenager, Arthur had constructed an amateur radio station using purchased components, make-shift materials and his own ingenuity. Arthur’s family had moved to a new home at 514 Fairview Drive, and his equipment moved with him. |

|

circa 1925 |

By the age of 15, Collins had communicated with other amateur “hams” in the United States and many foreign countries. The custom of exchanging postcards after a contact was made had already been established in the amateur world, and one wall of Collins’ attic room was covered with so-called QSL cards. One card from Australia came from a radio operator who regarded America’s prohibition of alcohol as a joke. “How does it feel to stay sober?” were the words the Australian ham wrote to 15-year-old Arthur. And during a contact with a person in Chile, the South American operator asked to be excused from the radio conversation because a volcano was erupting and interfering with the talk. “He referred to it as if it was in his backyard,” Collins told a Cedar Rapids Gazette reporter in 1925. |

|

The reporter, Gladys Arne, had gone to the Collins home to talk with the 15-year-old boy because he had made a radio contact that put him on the front pages of newspapers all over the country. During the winter of 1924-25, Collins had become familiar with John Reinartz, a 31-year-old German immigrant who was prominent in radio circles because he developed a “tuner” or receiver capable of predictable selectivity and reception. Reinartz had authored several articles on the subject for radio magazines. Reinartz and Collins carried on experiments, particularly in the use of short wavelengths. Because of Reinartz’s radio success, he was chosen as the radio operator for a scientific expedition to the continent of Greenland. The MacMillan expedition set sail from the coast of Maine on the ships Bowdoin and Perry in early 1925. One of the explorers was U.S. Navy Lt. Cdr. Richard E. Byrd. The plan was for the Bowdoin to make daily radio reports to the U.S. Naval radio station, but because of atmospheric problems, the land station in Washington, D.C., was unable to consistently receive Reinartz’s messages. Then word spread that a 15-year-old boy in Cedar Rapid’s had made contact with the expedition. Throughout the summer of 1925, Arthur Collins accomplished a task that even the U.S. Navy found difficult. Using a ham radio that he himself had built, he talked by code with Reinartz in Greenland night after night. His signals reached the expedition more clearly than any other. After each broadcast, young Collins took the messages from the expedition down to the Cedar Rapids telegraph office and relayed to Washington the scientific findings that the exploratory group had uncovered that day. Collins’ exclusive contact with the expedition soon became a nationwide news story that won him acclaim as a radio wizard. The August 4, 1925 Cedar Rapids Gazette told the story: One week later, a follow-up article in the Gazette concluded: “Though only 15, he is true to his trust. For he hopes to realize great radio ambitions, by and by.” At the age of 16, Collins was asked to write a technical article for Radio Age which was published in the May, 1926 issue. One statement in that article foreshadowed the motivational force which was to lead him to “great radio ambitions.” “The real thrill in amateur work comes not from talking to stations in distant lands … but from knowing that by careful and painstaking work and by diligent and systematic study you have been able to accomplish some feat, or establish some fact that is a new step toward more perfect communication.” Arthur’s reputation in the radio world grew. Radio operators around the country who had heard about his contacts with the MacMillan expedition wrote to him to ask how he did it. |

|

|

Collins continued his electronics education by taking courses at Amherst College in Massachusetts, Coe College in Cedar Rapids, and the University of Iowa in Iowa City. In 1927, he and two friends organized an expedition of sorts of their own. Collins, Paul Engle, and Winfield Salisbury outfitted a truck with short wave transmitting and receiving equipment and took a summer trip to the southwest states. Using power of 10 watts they conducted experiments in connection with the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C. Leo Hruska stayed behind in Cedar Rapids to operate the base station for the study. Like Collins, both Engle and Salisbury would later go on to achieve recognition in their particular chosen fields - Engle as a poet and professor at the University of Iowa, and Salisbury as a noted physicist who would make significant contributions to studies initiated by Collins. In 1930, Collins married Margaret Van Dyke. By the end of 1931 he had set up a shop in the basement of their home at 1720 6th Avenue S.E., previously the home of his grandparents. Arthur began to produce transmitters to order. |

|

|

When the depression hit with full force in 1931, 23-year-old Collins turned his hobby into a vocation. “I picked what I was interested in,” he told Forbes magazine years later, “and looked for a way to make a living.” This was the first time radio transmitting apparatus, of any power output, was available for purchase as an assembled and working unit. In fact, components were hard to come by; they varied widely in characteristics, and there was little, if any, pattern to their construction. Most hams had their radio equipment scattered around a room, usually in a basement or attic where the sight of tubes and wires wouldn’t clutter up living areas of a home. Their equipment was strictly functional, almost to the point of inefficiency. Collins’ ham gear was designed to eliminate the clutter by packaging the equipment in neat units. The concept proved that correctly engineered construction not only stabilized the circuitry but also made its behavior predictable. Collins designed circuits, fabricated chassis, mounted and wired in components, tested, packed and shipped each unit. Because the gear was precisely engineered and well-built with the best parts available, it gave years of trouble-free service. A later article in the New York Times quoted a ham as saying, “Collins brought us up from the cellar and put us into the living room.” The industrial philosophy of Collins products “quality” was established at the very start. The first advertisement for this new line of products appeared in the January, 1932 issue of QST, with the firm name given as Arthur A. Collins. Two issues later, in March, 1932, the firm name appeared as Collins Radio Transmitters with Arthur’s name and call number below. Both notices were two-inch advertisements, but by May the size was increased to six inches. In October the first full-page ad appeared and by December, the firm’s name was listed as Collins Radio Company. Long-time friend Jiggs Ozburn recalled his first meeting with Collins. “I first met Arthur Collins at a ham club meeting at his house (factory in basement). I hadn’t finished high school and he hadn’t finished college (he never did). Art had been making ham transmitters for about a year. He was tall and slender and very quiet. He came from a well-to-do family whose fortune was taking a beating in those depression years, so Art was pretty much on his own.” The Great Depression, which began after the stock market crash in 1929, was having a devastating effect on the Collins Farms Company. In 1931, M.H. Collins sold the firm to an east coast insurance company. Arthur originally started his company as sole owner with only one employee, Clair Miller, who had just been graduated from Iowa State College. But as his business grew, he added personnel, including some who came from his father’s farm company. Among them were John Dayhoff and Ted Saxon. Orders came in and the company grew. In 1933, Collins Radio Company moved out of the basement factory and into leased space at 2920 First Avenue in Cedar Rapids, now headquarters for the local Salvation Army. Business in general in 1933 was not good, to put it mildly, but radio had come of age, and Collins recognized the need for advancement in the radio communications field. One Saturday morning that year, Collins telephoned Arlo Goodyear and offered him a job for two months if he was willing to work on Sundays. Out of work for months and with a wife and baby, Goodyear jumped at the opportunity. “There it was in the middle of the Depression and he was asking me if I minded working on Sunday,” Goodyear later wrote. “I would have worked on Shrove Tuesday.” Collins and his work force of one arrived at the building only to discover that neither had a key to get into the basement area, where the company was to begin production the next morning. Collins looked at the door, looked at Goodyear, and said, “Well, we’ve got to get going. Catch me so I won’t fall on my head.” Collins charged the locked door and the new plant got underway with a bang and a shattered front door. On September 22, 1933, with eight employees and $29,000 in capital, Collins Radio Company became a corporation under the laws of the State of Delaware. At that time Delaware had some of the most modern corporation laws in the country, and many businesses were officially organizing there, although their actual facilities were located in other states. (On May 13, 1937, the company reorganized as an Iowa corporation.) |

|

| Reprinted from The First 50 Years … A History of Collins Radio Company by: Ken C. Braband. ©1983 Communications Department, Avionics Group, Rockwell International, Cedar Rapids, Iowa |

|